“The Kayanic Arts of Borneo: Adventures in Chronology and Authenticity” by Antonio J. Guerreiro & Steven G. Alpert

The Kayanic Arts of Borneo

Adventures in Chronology and Authenticity

by Antonio J. Guerreiro & Steven G. Alpert

Note:

This article on Kayanic arts was originally written and submitted for publication between 2015 and 2016. Because our piece has not yet made it into print we have decided to feature it on Art of the Ancestors. An updated, longer, and more rigorous exploration of this topic is currently being prepared for academic publication. It is our hope that the insights and materials assembled here will be regarded as a sincere contribution to the alluring, and at times, mystifying subject of the artistic heritage of the island of Borneo.

— Steven G. Alpert

Borneo has always occupied a special place in the Western imagination. With the discovery in the 17th century of the orangutan (orang hutan: the man of the forest), it became, like the Dark Continent of Africa, a place where the divide between human and animal, civilization and the primeval forest, facts, and fiction still continue to confront one another. This fascination was further fueled in the 19th and 20th centuries by travelogues, scientific expeditions, and colonial literature. Even today, there is still a sense of mystery and exotic adventure associated with the rain forests, wildlife, and indigenous peoples of the world’s third-largest island.

Borneo's tribal history is a complicated and dynamic mosaic of continual migrations. In addition to knowing when objects came out of the field and to which group they belong, it is also crucial to know when that particular area was settled if we are to date pieces accurately. A careful stylistic analysis of the corpus of genuine material in private collections and museums predating the advent of sophisticated ateliers of production is de rigeur to this process. To better understand this material as 'art' involves not just aesthetic sensibilities but a deep appreciation for the value of many decades of scholarship based on genealogies, oral traditions, and recorded history.

The focus of this article is an introduction to the carving traditions of a loosely extended group of Dayak peoples (a generic term for indigenous tribes of Borneo) that through language, history, and cultural identity are often referred to as being “Kayanic.”

Since it is a topical issue of importance, we will also briefly explore the radiocarbon dating of wooden Borneo artifacts while illustrating why using this methodology as the principal basis for authentication, art historical inquiry, and chronological theorizing is deeply problematic and has led to spurious material being regarded as genuine.

A Brief Outline of Kayanic History

With the exception of small pockets of related groups in Sarawak and Western Borneo, most Kayanic peoples live in a vast swath of territory in eastern Borneo, now known as “Kaltim” or East Kalimantan. Based on recorded traditions, field notes, and published sources from the 19th century onward, the Kayanic peoples hail from Northwest Borneo, the lower Baram or Telang Usaan area of Sarawak and Brunei Bay. The tremendous linguistic diversity found in the Baram and the surrounding region, with at least four main language groups, further suggests a place of seminal importance from where various peoples moved in the course of time to Southern Sarawak and East Kalimantan.

From there, they followed the watershed through Long Banga and the surrounding mountains to reach the Apo Da’ah. Eventually, they went down to the Bahau River, which they reached in the late 16th to the early-mid 17th centuries according to their genealogies. (See map). The cause of these long-range migrations from the Baram to the Kayan and Mahakam Basins was fueled by an aristocratic system of chiefs (hapoy/hipuy) whose competitive drive to expand trade and create economic alliances, coupled with the superior military capacity of the Kayanic Modang/Manga’ay, set them apart from other ethnic entities living in the interior of Borneo. The former created an efficient grade-ranking system related to headhunting centered on the institution of men's houses. This model was assimilated by their neighbors, including some of the Kenyah and Kayan and Bahau Saa’ (Guerreiro 1998).

The development and the obvious advantages of possessing metallurgical knowledge by these same peoples were directly connected via trade to Brunei's north coast, where the smelting, casting of bronze, brass, and the forging of tempered metals reached its zenith in Borneo. Reflecting the Sultanate of Brunei's power and exposure to a broader world, it is not surprising that the Kayanic peoples’ heirlooms (pusaka) are often bronze statues or small ritual objects and tempered swords blades (Guerreiro 2002; Harrisson: 1964,1965). The Kayanics may also have produced high-quality weapons on orders from Brunei during a long period dating from around the 14th to the 18th centuries. In return, they received Brunei cannons (i.e., swivels called lila or meriam, depending on their size).

Migrations of Kayanic peoples towards the Mahakam watershed followed two main routes. In the mid 18th century, under the leadership of Bo’ Kwing Irang Aya' (Singa Melön), the Western route was used from the Apo Lallang to the main Mahakam basin. Later, the powerful Long Gelaat (Modang) under the leadership of Po’ Ding Tong (known as Bo’ Ding Doh in Kayan Busang language) followed the Eastern route from a tributary of the Ogah to the mouth of the Gelaat and then onto the Boh River. They pushed the less numerous Bahau Saa’ groups downstream towards the middle Mahakam, where they eventually settled the main part of the upper Mahakam up to Kayaan territory.

The Busang and Long Glaat territories occupied the best agricultural lands along the main branch of the Mahakam, extending from below the rapids in the current Uma’ Mehak area to the Sungai Dini upriver. When the Kayaan Uma’ Suling arrived in the area from the Baleh around 1830, they first settled on the eastern tributaries of the Mahakam, the Meraseh, and Langasah rivers. At this time, small linguistically diverse Busang groups were still scattered on the tributaries of the upper Mahakam and at Uma’ Pala’, Uma’ Palo, Uma’ Urut, Uma’ Sam, Uma’ Mehak, Bang Kelau, Uma Tepay, Uma’ Lekué, Uma’ Wak on the Boh. These groups submitted one after the other to the Long Glaat and then came to reside in their villages on the main river.

In short, the “ethnic territories” of the region stabilized around 1830-40 (compare Tromp 1889:290-292). Later, the Long Glaat chiefs’ daughters' marriages with the ruling hipuy families of each area consolidated alliances between different groups and villages. Frequent headhunting raids by the Iban from the north, culminating with the large expedition (bala) of 1885, developed a sense of unity and territorial integrity between the varying inhabitants of this part of the upper Mahakam that remains to this day.

Kayanic Art in Museum Collections

The earliest colonial era ethnographers and explorers of central Borneo ca. the 1870s to the 1920s, such as Carl Bock (1878-1879), A.W. Nieuwenhuis (1894, 1896-1897, 1898-1900), and Charles Hose (1884-1907), collected many sculptures, wood carvings, and artifacts from the Kayan, the Kayanic Bahau and Modang peoples of the Mahakam, especially containers, swords, masks, shields and longhouse panels, and doors. As far as we know, they did not collect large ironwood sculptures or flat guardian figures.

The most outstanding Kayanic collections in Europe are in the United Kingdom at the British Museum, the Cambridge Archeology and Anthropology Museum, Pitt Rivers, Oxford, and the National Museum of Scotland. In the Netherlands, where many museums have holdings, the most well-known are the collections at the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, the Wereldmuseum in Rotterdam, and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. Other museums in Europe, such as Basel (Museum der Kulturen), Vienna (Museum der Wereld), Dresden (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen), Cologne (Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum), Budapest (Neprajzi Museum), Oslo (Kulturhistorik Museum), Stockholm (World Cultural Museum) and the Pigorini Museum in Rome also steward numerous Kayanic items. In Switzerland, the Lugano Museo delle Culture contains Borneo sculpture from the Serge Brignoni bequest, and the Barbier-Mueller Tribal Art Museum in Geneva still has important items. However, most of its Dayak collection was acquired by the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris (2001).

Other significant collections found in the United States include the Dallas Museum of Art, the Yale University Art Gallery (Thomas Jaffe collection), The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the de Young Museum in San Francisco, The Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology (Furness collection 1896-1898) and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (W.O. Krohn collection, donated to the Museum in 1925).

Lastly, in Asia, the Museum Nasional in Jakarta and the Sarawak Museum in Kuching, East Malaysia, founded in 1888, also house rare Kayanic pieces, including iconic kelirieng and salung burial posts. The Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore has outstanding Kayanic pieces that can be seen to good advantage in their newly reinstalled galleries. The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) also has several Kayanic sculptures of distinction. However, many related artworks, either in terms of statuary or large architectural items, are still to be found in private collections primarily in Europe and the United States.

Kayanic Artistic Traditions

The knowledge of metallurgy among the Kayanic peoples enabled them to make excellent carving tools such as awls and drills (kelivo), axes (asé, say), adzes of various shapes (bikung), and knives of various sizes (yu, malaat, kuu’). The awl and drill were primarily used for architectural pieces and canoe prows. Broadly speaking, the various Modang peoples of the Northern tributaries of the Mahakam have maintained their distinctive carving styles without direct Kayan or Bahau Saa’ influences. Much of the art illustrated for this article originates from the settlements erected there, circa the 17th/18th through the early 20th century.

From a stylistic point of view, these pieces are markedly different from known sculptures from the Kayan and Kenyah peoples in Western to Central Borneo and of those Northern Kayanic groups in Eastern Borneo (Tembau, Ga’ay, Mraap). They are not known for producing large anthropomorphic statues. Instead, the latter mostly carved funerary structures: platforms, mausoleums, coffins, and posts. These carvings were connected to secondary burial practices. However, after two centuries or more, most of these edifices have collapsed and been consumed by the forest.

Statues and coffin ends are typified by a large head that characteristically displays a concave face with bulging eye sockets, a protruding jaw, and sometimes a high rounded or oblong-shaped head. Some of the plastic features of the so-called “heart-shaped” face found in Borneo and other regions in Indonesia may have been inspired by the Bronze Age culture of Dongson, which evolved in Vietnam around the middle of the last millennium B.C.E.. Dongson artifacts, and those that were later made locally in Indonesia, most notably impressive bronze kettledrums, were highly prized by their owners. Trade in these wares helped to spread a number of recognizable artistic motifs throughout the archipelago. Other “Dongson” elements also appear in the repertoire of small bronzes and brass items cast in Borneo, including turtles, birds, jars, and anthropomorphic figures. In a sense, these are a testament to the longing for and the transformative power of metal. In Borneo, the latter are not ‘prehistoric’ or even ‘proto-historic' bronzes, as they were probably made in and around Brunei from the 14th to 19th centuries.

Within this crucible, the Modang developed their dynamic carving style over time. Slaves captured in raids by the Modang commingled with local commoners (panyin, pengin), but rarely with the aristocracy of Kayaan and Long Glaat. Thus, the resultant blending of the Kayaan, Kayan Busang, and Modang (Long Glaat) into multicultural villages in the upper Mahakam produced a synthesis of Kayanic styles that affected related peoples such as the Aoheng (Penihing).

In the Middle Mahakam area, the Bahau Saa’ also produced exquisite items that integrate Modang and Kayan components into their own aesthetic. Most striking are the hardwood baby carriers (katung) and wooden support struts supporting rattan versions, ritual posts (jihé), and carvings connected to the longhouse: panels, lintels, doors, finials, ridge, and stairs (saan, hesuyn). In connection with headhunting rituals, special posts (tapatung) were carved to memorialize the event. They depict an entire human body or only a human face at the top of a plain post. Another category of ritual carvings made by Bahau Saa’ included flat anthropomorphic posts or panels engraved in high relief that are commonly referred to as 'guardian figures.' Some of these were carved in an ajour or openwork style that was integrated into fences or placed near mausoleums and rock shelter burials.

It should be mentioned that the decorative motives (kalung) on Kayanic art appear in many guises. Designs such as the tiger-dog (aso’ lejau/sau lejiu), the monkey (kuyat, bruk), the lizard (kawuk), the dragon (la ngunan), or the large spirit face (naang beraang), the thunder god’s face (naang belarè’ ) or the mask (hudo’) are readily recognizable and broadly similar among the different Kayanic groups. Generally, the carving's main figures are linked by intricate patterns of spirals and curvilinear designs (kelawit). A category of hybrid zoö anthropomorphic spirits is also characteristically found in Kayanic sculpture. They include the psychopomps carved at the ends and on the sides of coffins and various burial structures (burial platforms, salung orblah, bilah Mausoleums).

Other Kayans, such as those living in West Kalimantan or Sarawak, exhibit much less sophistication in woodcarving with one major exception: the imposing kelirieng/kelidieng burial posts used in aristocratic secondary burials among the Punan, Kejaman, Lahanan, Kajang, Berawan, and some Kayan communities in the Baluy area (Upper Rejang) of Sarawak. Their counterparts in Eastern Borneo are less ambitious both in regard to scale and design. Generally, panels, lintels, and doors, partly carved in low or high relief, in addition to smaller items such as stools, work boards, and baby carrier struts, lids, and stoppers for containers and jars are common to the different cultural Kayanic groups and their neighbors in central Borneo (Kajang, Kenyah and Sebup). The Kayanic influence in decorative panels, especially in lintels, doors, and wall panels or spirit masks, was also assimilated by some of the Kenyah in the Apo Kayaan and Sarawak. Still, this influence did not generally extend to sculpture in the round, such as large ironwood memorial effigies for chiefs and aristocrats or funerary guardian statues.

Material

Kayanic peoples use ironwood and other hardwoods for carving, although shields, masks, and utilitarian items are also fashioned in lighter wood such as pelai/pulai (Alstonia spp.). Back in the 1970s, Dayak informants would relate to researchers or field collectors that the surfaces of outdoor ironwood statues began to display worn rivulets and deep cracks within 80-100 years. Further, they asserted that they seldom survived much more than 150-200 years of open exposure in the forest. Of course, this rule of thumb varies depending on the exact timber species, where the items were found, and whether they had some form of protection from the elements.

Known locally as belian or ulin, ironwood (Eusideroxylon zwageri, T. de B.) is primarily used by Dayak peoples for carving statues and as a building material (posts, crossbeams, beams, and house framework). Other species of hardwoods are also utilized, and these can be classified into two categories; hard and semi-hard. Besides Borneo's ninety species of ironwood, hardwoods such as menggeris (Koompasia spp.) are used for sculpture, spinning tops, and seats, while selangan batu (Shoreasp.) is used for crafting posts, beams, crossbeams in longhouses. Semi-hard kapur (Dryobalanops spp.) provides timber for making walls and flooring. Bengkirai (Hopea mangarawan) is a good wood for interior work or for interior house posts, but it cannot stand for more than twenty years out in the open. One finds it mostly used for items such as lids and stoppers, doors, and panels of a lesser quality of craftsmanship. It is important for students of this material to appreciate the Dayak’s knowledge of which wood to use for a specific application. This discernment is something of great value that is handed down from father to son and from expert to novice.

Riverine and Funerary Carvings

In the 1970s, a significant number of Dayak statues began to appear on the local and international art market. The burgeoning interest in this material just happened to overlap with the onset of intensive logging, periodic droughts, and increased erosion along the banks of the Mahakam River and its main tributaries, the Belayan, Kelinjau, and Telen-Wahau Rivers. It was at this time that the first antique riverine pieces were discovered and subsequently sold.

Authentic riverine pieces are miracles of survival. Traditionally, for defensive purposes during the era of headhunting, villages were established on the main rivers at the confluence of small streams and tributaries. When the course of these streams and rivers became altered, or when the water levels drastically changed, old fallen carvings became exposed. These items were comprised of embellished architectonic fragments, including a few house and mausoleum posts, and even fewer carved figures that were always found in damaged condition. The number of fragmentary figurative sculptures that appeared during this time, c.1978-1990, was relatively small, not more than 20-30 known examples. Whenever the best of these pieces came onto the market, sometimes in Jakarta, but mostly in Bali, it was something of a celebratory event for the entire local community of professional dealers in Dayak art. The dealers who had located the best pieces, approximately where they had been found, who had brought them to the marketplace, and the eventual buyers’ identities became public knowledge and part of the era’s lore.

One of the earliest of these riverine pieces, and the very first Dayak piece to be carbon dated by a professional art dealer (Alpert: 1981), is now in the Dallas Museum of Art. Its calibrated carbon date was 1040+/40 A.D. When samples were shown to the then reigning expert of Borneo hardwoods, Dr. Carl de Zeeuw. He initially opined that the carbon date was irrelevant to the statue’s actual age. Later, after learning that the wood was Koompassia excelsa (Leguminosae), one of the few species of Borneo hardwoods to have ever been studied over a long period of time, Dr. de Zeeuw suggested that in his opinion, approximately 200-300 years should be added to the above C14 date. Subsequently, the piece was dated at “13th century or later” (de Zeeuw and Alpert in Alpert and Schefold (eds.) 2013:135). This piece is one of the few well-documented pieces found on the Telen River. Its architectural function as a suspended figure is also clear, as seen in Raja Dinda’s family mausoleum (blah) at Long Way (now renamed Long Bentuk) on the nearby Kelinjau River, which was drawn by Carl Bock in 1879 (Guerreiro 1983/Alpert 2013). In the 1970s, fewer than one hundred years later, when travelers searched for this magnificent structure, all that remained of its former glory were rotted nubs that indicated where the structure's main posts had once stood.

The foregoing is an example of a clearly genuine, old piece whose C14 date does not align with the historical record of the Modang people who presumably created it but who did not settle in this area until c.1680-1700. How might these facts be reconciled?

There are three possibilities:

A. The piece belonged to an unrecorded enigmatic group that lived in this area before the Modang.

B. The Modang Wehea could have brought it with them from the Apo Kayaan area (Bo’ Kejien) when they migrated south.

C. Or, most likely and most logically, the dating of the piece is incorrect, and it was most likely created from the late 17th to the early 18th century.

On a stylistic basis, the iconography of this piece combining a colossal head and a slender curved body recessing backward evokes some later aesthetic developments among the Modang. While this masterpiece is stylistically as old as is presently conceivable for a figurative carving from this area to be, until more information is available or until related pieces can be studied within an archaeological context, we would posit that its date should be revised to synchronize with Modang history and migration patterns.

Riverine pieces sometimes also display a kind of pre-fossilization of the wood, as evidenced in an ironwood burial offering post showing rare “double images” of spirits and lizards, currently at Paris’ Musée du quai Branly. This large piece, not unlike Dallas' riverine Modang statue, lay in mud on a riverbank in the upper Telen for approximately three centuries (Guerreiro 2008b). While surfaces obviously vary in genuine riverine pieces, they always reveal contiguous evidence of wear from exposure in an original context, punctuated with the effects of long being buried in sediments close to a river’s banks for an unspecified period. The most salient parts of pieces that are not genuine are usually too finely preserved, and the transitional areas where erosion always occurs is seldom convincing. Nature works a landscape according to her own rules, rules that do not care about our aesthetic desires or predilections.

In contrast, authentic riverine pieces and carvings found in protected rock enclosures or cave sites, even if they are well-preserved, display telltale signs of wear or breakage. We attribute most of these pieces to little known Kayanic or Kajang groups living on the fringes of the Apo Kayaan plateau from the 17th to 18th centuries. The wood used is ironwood or a lighter species, the reddish arau/aro (Elmerillia tsiampacca). These carvings were most likely intended to keep the deceased safe from evil spirits and to further assist them in their journey ‘to the land of the departed souls.’

Burial sites are comprised of coffins (lungun), ironwood platforms (jin juhan), posts (jihé’, jehoè), beams (tavé), and protective statues (tepatung) that are usually typified by the carving of anthropomorphic and/or zoomorphic figures of the Kayanic peoples. These range from the time when a group first appeared on a river system to recent times. The wooden structures of the burial monuments, such as mausoleums of the salung or the kelirieng type, show different wear patterns according to their location on a river’s bank or a protected rock face. In the latter category, one should mention the first Aoheng (Penihing) panel recorded in situ in 1896 by Nieuwenhuis’ expedition photographer, Jean Demmeni, at the burial ground of the Aoheng (Penihing) on the Cihang River at Long Nanya. (Nieuwenhuis, 1904, vol I: plate 74, 376). In the Upper Mahakam, similar protective figures are also carved on both ends of the Long Glaat and Busang coffins.

During the 1950s through the early 1970s, both Presidents Sukarno and Suharto forbade the construction and use of longhouses, especially in the hinterland and border areas of Kalimantan Timur. This also coincided with the last traditionalists being pressured to convert to either Christianity or Islam. It was in this context of social change that older carvings were sold to Malay/Bugis and Chinese middlemen. Later the opening of the inland regions during the timber boom, locally known as Banjir Kap (“flowing the timber down the river”), made more able carvers turn to other jobs, thus disrupting the production of sculpture for their communities. While this led to a fallow period for carvers, once the chisel was taken up again, there was some verve and artistic confidence to the items they produced. It is interesting to note that some doors, panels, and a few ajour styled post figures were also carved at this time for sale by traditionally trained Dayak carvers who, just a few decades earlier, had been carvers of genuine ritual pieces and decorative embellishments for longhouses. At first glance and in some ways, these carvings may appear to be as refined as the originals: however, when one is thoroughly acquainted with the corpus of material, particularly with masterpieces, it becomes apparent that modern carvings executed outside the context of older ritual functions lack a certain 'agonal' edge, are softer and have a less overall visual impact than antique works. (See Alpert 2013: 123).

Arguably, the most iconic of all riverine statues is a Bahau or pre-Bahau guardian figure (tepatung) that was found along the banks of the Wahau River. This unique, though often copied, piece was first published in 1990. It since became perhaps the most influential single statue to inspire the birth of an industry. Over the past 40 years, the skill set for reproducing ancient-looking riverine statues based on a few genuine items has gradually become much more sophisticated.

Examples of these objects may initially appear to be interesting. They can be found on websites devoted to Borneo, at prestigious art fairs, in diverse seller's catalogs, and most, unfortunately, in a few museum collections. Although there is enthusiastic support for these pieces by their proponents, they are completely undocumented. Their claims for great age, however, which are based solely on radiocarbon dating, have not been challenged in dialogues with dissenting experts or within academic forums.

C14 and the Dating of Wooden Sculpture from Borneo

It is common knowledge that from the late 19th century onward, curios from Borneo have been produced for Westerners. Commenting on the Indonesian art market in 1989 in a New York Times article, Bernard de Grunne, who then worked for Sotheby's, was quoted as saying, "The better things came out in the 1970s. Today, they make incredibly good fakes." Since then, a highly-skilled atelier-based industry has developed, particularly around the production of so-called 'archaic' looking statues and coffin ends. It is almost certain that the ateliers dedicated to producing ersatz Dayak material know well that C14 testing is being used to attempt to validate these carvings. Reliance on radiocarbon testing can also create confusion regarding the ranges of age of authentic wooden artifacts by making them possibly seem to be much older than their actual dates of manufacture.

Let us be absolutely clear by pointing out that laboratories date the age of a wood sample, not the point in time when a statue was actually carved. It is generally not within their purview to make pronouncements on whether a piece of art is authentic or not. That said, in some cases, C14 may help to identify recent forgeries. The most prestigious dating labs, like the ones at Arizona University or at Oxford, are primarily academic rather than commercially oriented and will provide detailed reports on all aspects of samples they have analyzed.

In layman’s terms provided by Dr. Greg Hodgins, the Director of the University of Arizona's AMS Facility, wood harvested from just under the bark would provide us with the date of the felling of a tree – its death. Conversely, the center cellulose core samples represent the birth, hence the oldest part of the tree that becomes incrementally younger (newer in terms of date) as you move from the center of a tree outwards towards its bark. Given that many of the Borneo pieces now being dated are fashioned from dense tropical hardwoods that grow very slowly, on average approximately 30cm in diameter every 100-120 years, Dr. Hodgins wrote, “If the species are long-lived (as opposed to short-lived), then uncertainties about the relationship between an object's carving and its radiocarbon content abound.”

Radiocarbon dating requires specialized analytical expertise. Within the community of scientists, there must be access to the full analysis of a C14 report. To illustrate this point, consider below the two Modang Wehea ancestor effigies (bo' jeung) of a type that were once placed by the edge of the river in front of a great house. The figure on the far right (white background) is the finest surviving example of this genre in terms of age and aesthetic power. Based on all we currently know, the authors would date this piece to the 18th century according to its stylistic qualities and where it was found.

On the other hand, the piece to its left (black background), in our opinion, is clearly later and not as accomplished as a work of art. It was advertised in 2004 as having a C14 date of 1422-1642 AD with the added comment, “old as expected.” What does this mean, exactly? Does ‘old’ here refer to the age of the wood itself or to the statue's actual age? The wording is ambiguous, and the meaning unclear. As previously stated, radiocarbon dating can only reveal the age of the material, not when a statue or architectural artifact was actually crafted.

Clearly, the second statue to the left (black background) is a good piece, although we would respectfully date it as most likely being from the 19th century. The evident disparity between the published date and our assessment can best be explained in two ways:

A. The statue is from the core of a slow-growing ironwood tree, and the cutting away of layers from the bark inwards adds an unknowable number of years to the putative date.

B. The younger range of the carbon date, within a scientifically acceptable margin for error, abuts or possibly overlaps a period from c.1680-1950 AD that is commonly referred to as the “Stradivarius Gap.”

Writing about this period, the noted radiocarbon scientist, A.J.T. Jull, states that, “The number of rapid fluctuations on C14 content due to solar activity, and also due to the addition of a lot of “dead” carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels, makes precisely calibrated ages in this region impossible.”

If an ancient tree were recently felled, and sadly this has happened many times according to informants, and if a statue was subsequently carved from its core, we know that the C14 result will reflect its age of birth – but we also wondered whether there might be some telltale sign of tangible modernity within the sample. In response to our query, Dr. Hodgins replied, “Regarding your question about trees whose lives spanned the dawn of the nuclear age, it is absolutely true that one could harvest a tree after 1955, a tree whose outer post-1955 tissues contained bomb derived radiocarbon but inner tissues were bomb carbon-free. As you suggest, one could produce a sculpture from that tree that was free of elevated radiocarbon levels because all traces of bomb derived radiocarbon were carved away. This, in a nutshell, is the challenge of radiocarbon dating wood from all sculptures in an effort to understand when they were carved. Yes, cunning modern fakers could very easily fell large trees and use the inner wood to produce a sculpture without any post-1955 wood in them.”

This might explain some of the more mystifying C14 results that have been adopted and heralded by a few dealers and collectors. These findings, however, if they are accurate, would necessitate a scholarly reassessment and the rewriting of Southeast Asia's prehistory. Old wood is generally sourced from riverbanks and re-carved by forgers. Bog-like environments are sometimes anoxic so that normal biological decay processes cannot take place. Dr. Hodgins goes on to write that someone with access to bogwood, “…could probably carve sculptures with wood from any time period over the last few thousand years. There are companies in New Zealand who will make and sell you a fountain pen, or a toilet seat from Bog-Kauri wood, with a certificate saying that it is at least 3000 years old.” Yale's Dr. Ruth Barnes has also observed, “a wood carving may be done many years after a tree has been felled, or may reuse material from a different context. The date will reflect the period of growth of the material, which may be different from the time of turning it into an artifact. To put it bluntly, radiocarbon dating of a wood sculpture is useless unless the context of its recovery is otherwise well documented".

Beyond Borneo, controversies regarding the utility of radiocarbon dating as a tool of art historical inquiry are abundant. This fact is epitomized by a relevant tale of caveat and caution that can be gleaned from the experiences of the National Gallery of Australia. In 1978, the NGA purchased a remarkable Maori canoe prow ornament. In 2007, samples were taken from underneath the base of the carving and subsequently dated by two separate labs. The first lab reported a calibrated C14 date range from 1314 AD to 1357 AD, adding a 95% confidence factor at 1388 AD to 1434 AD. The second gave a calibrated age range of 1410-1452 AD placing both lab results within a contiguous period.

Juxtaposed to these dates was the simple fact that this same carving had been recorded in a pencil drawing by the artist, George Angus French, at Porirua Harbor in 1844. His handwritten notations describe the work as belonging to the famous rangatira (leader and war chief) of the Ngati Toa tribe, Te Rauparaha (1760’s-1849). This drawing, coupled with an 1847 engraved illustration of it that appears in The New Zealander (plate XLII, page 98), makes it clear that this particular inner canoe prow ornament was most likely carved as late as ca 1835 – a difference of between 400-520 years between what radiocarbon results suggested and the historical record.

The Carving and Processing of Ancient-Looking Dayak Curios

The reproduction of antique-looking pieces of Dayak art has become a profession with its own traditions and specialized techniques. Aside from Dayak carvers, the most accomplished carvers of contemporary works that are fashioned to look antique are mainly Buginese, but also Javanese and Chinese, whose families have been living in East Kalimantan, often for multiple generations. Some carvers have married Dayak women from the interior. They are inspired by photographs of genuine pieces found on the Internet, vendor catalogs, and some auction houses. They combine chemistry, some modern tooling, and a surprising melange of high and low-tech methods based on years of experimentation in combination with a grand knowledge of jungle lore. The process of creating an ersatz ‘antique’ piece can take between 3-5 years.

The first competent reproductions of Kayanic material began to appear in the late 1970’s. The rarity of genuine Kayanic pieces created an increasingly fervent demand for curios and ‘reproductions,’ which have been routinely supplied by ateliers based outside of Kuching (Sarawak), Samarinda (Kaltim), Bali, and Makassar (on Sulawesi island) for more than twenty years. More recently, an old friend of mine who is in the vanilla business was surprisingly offered a wide array of Borneo styled statues by former carvers living in remote areas east of Palu (Sulawesi) who were forced to return to their agricultural roots when their orders for statues stalled. What follows is a recipe presented to us by a local, with the understanding that each carver or atelier has its own secret recipes and working techniques:

Old, plain, riverine wood or the core of a newly felled ancient tree is carefully selected, carved, and sandblasted before a series of various acids and chemicals are applied to its surface. In some cases, routing tools, much like dentist drills, are used to make fine lines or fissures on the wood’s surface. Afterward, the carving goes through a cyclical process of being wrapped and buried for periods of time, then put in the fast running water of jungle streams. It is meticulously cleaned, and most importantly, kiln-dried after each step. This cycle is repeated as many times as deemed necessary until the piece has a look and feel that pleases its maker. Periodically, and as the final touch, a carving is put in an upright position under specific trees to catch elements and detritus that will, it is hoped, affect the wood’s surface. At varying times in the process, a carving may be swathed in burlap-soaked chemicals or covered with natural substances to attract insects. Such surfaces are well recognized within the community of forgers. In responding to a recently published piece, one of our informants observed that the carving’s skin had been processed using a particular species of gambir (Uncaria gambir Roxb.), a plant that is an ingredient in a betel quid.

Conclusion

The intellectual property of the Kayanic traditions ultimately rests with the descendants of the Kayan, Bahau, and Modang master carvers whose ‘brand’ – the inherited flower of their ancestors’ art should not be subject to spoliation by the confusion and commingling of fine old pieces and more modern authentic ritual or cultural items with antique-looking modern impressions recently created for sale. In the words of M. Jones (1990:16): “When a group of fakes is accepted into the canon of genuine work, all subsequent judgments about the artist or period in question are based on the perceptions built in part upon the fakes themselves.” This quote and the observation that the profit-motivated production of spurious art exerts an unmerited influence has been well noted. (See Schefold 2001: Stylistic canon, imitation, faking: The Case of Siberut, (Mentawai, Western Indonesia). It is a reasonable assumption that serious students of the art of local traditions should appreciate the importance of the proper identification of heritage art, which, in turn, protects and honors the cultural identity of the peoples who created it.

Today, the carving styles of Kayanic peoples are still evolving. Dayak artists in East Kalimantan sometimes adapt to outside influences arriving from Java, Bali, or the West while still adhering to their traditional artistic canons. Since the mid-1990s, for example, a more naturalistic trend can be noted among the Benua’, Bentian, and Tunjung Blontang carvers. Such aesthetic evolution parallels the changing function of these statues as pieces that were once used solely as sacrificial posts have now assumed other more ornamental functions. Some are placed near churches or structures connected to tourism, such as guesthouses and reconstructed two-story longhouses. These contemporary works are produced by the same artists who still know how to carve traditional ritual posts (jehoè) or the Modang memorial effigies (bo’jeung) within a ceremonial context. There is a bright future for young artists there, as they continue to be trained under the watchful supervision of a tukang or master carver.

The practice of precisely documenting antique wooden sculpture ensures that items of bogus antiquity created by local and non-indigenous persons will become increasingly recognizable. By following this approach, authentic Kayanic art can be better understood and appreciated in the pantheon of world art. As well, the potency and importance of the older masterworks illustrated here should not be measured or judged solely on the basis of a C14 test. Instead, outstanding pieces should be appreciated within the parentheses of their own past and present cultural context, as indigenous arts are veritable benchmarks of memory, change, and challenge in traditional peoples' lives.

Antonio J. Guerreiro

Dr. Antonio J. Guerreiro received his Ph.D at EHESS in Paris (1985). After initially focusing on architectural, social and cultural anthropology studies, he later gained insight and expertise in museography. Dr. Guerreiro has researched Hindu-Buddhist iconography and architecture in Southeast Asia, and has since the 1980’s extensively published on Malay-Indonesian ethnic cultures with a special focus on Sumatra and Borneo. While lecturing in the field of material culture studies,- i.e. vernacular architecture and sculpture - Dr. Guerreiro has worked as a consultant for various museographical projects in France and abroad besides curating/co-curating diverse exhibitions. During the 1990s, he was a visiting scholar at the Department of Anthropology, University of Tokyo.

He is currently a Senior Research associate at the Institut de Recherches sur l’Asie (IrASIA, CNRS/Aix-Marseille Université, Marseille, France) and a member of ICOM-France (Unesco-Paris). He is also Secretary-General of the Society of Euroasiatic Studies at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris. In 2017-2018 he was a Research Fellow at the Sarawak Museum Campus Project (SMCP) and Heritage Trail project in Kuching (Sarawak, Malaysia). Dr. Guerreiro is still doing consultancy for the Museum while conducting research on woodcarving traditions, museum collections and the conservation of monumental structures of the Orang Ulu peoples of Sarawak. He is also actively engaged in researching colonial photography in Borneo (Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei, Kalimantan).

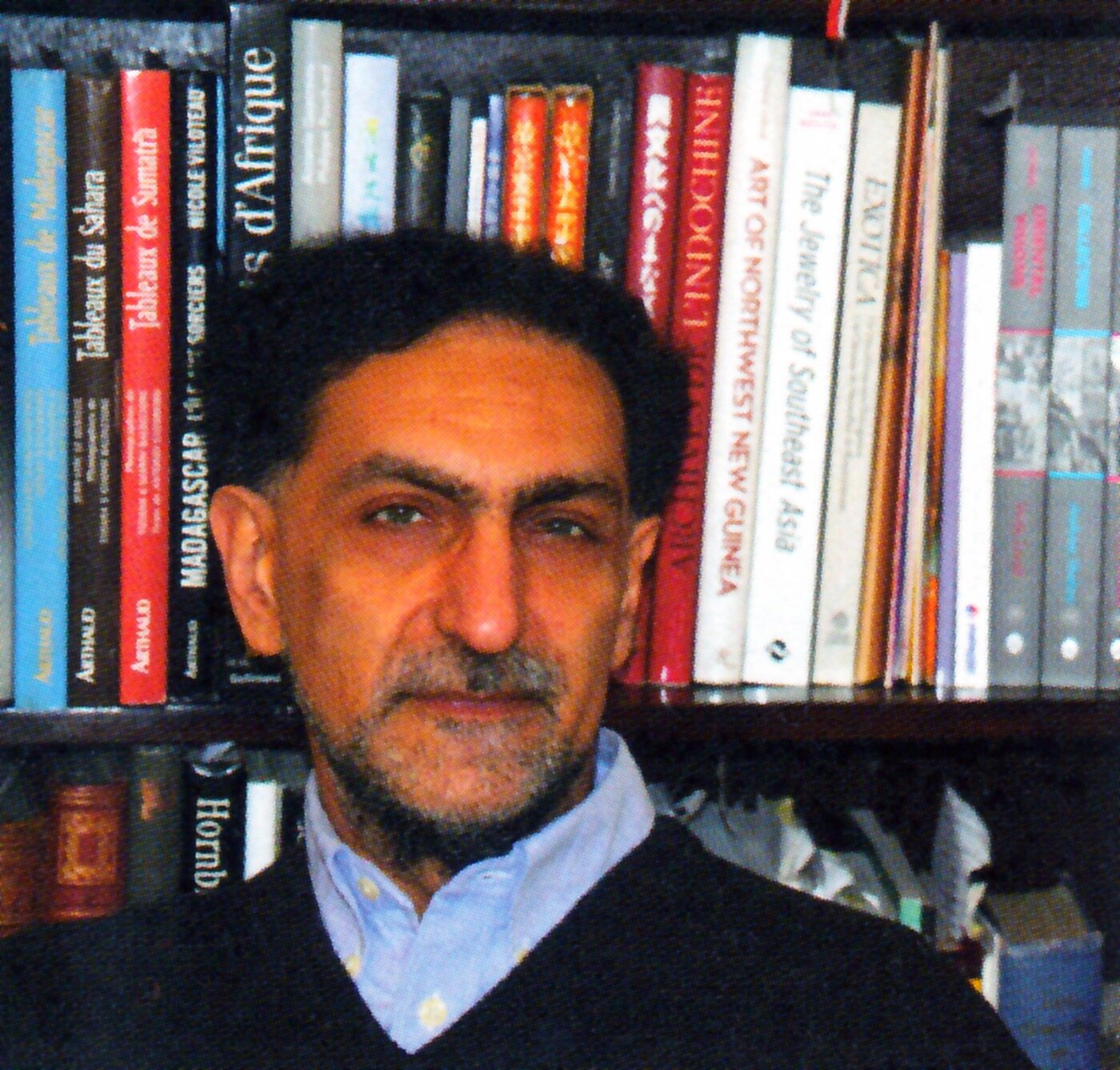

Steven G. Alpert

For half a century, Steven G. Alpert has been recognized as a leading collector, curatorial consultant, author, and philanthropist in the world of fine art.

A graduate of Wesleyan University with a dual major in Anthropology and Art History, Mr. Alpert was mentored by David P. McAllester, a pioneer in the field of ethnomusicology. Through study abroad at Auckland University in New Zealand, he received training from acclaimed scholars including Dr. Peter Bellwood, Professor Emeritus, an archaeologist known for his work in Southeast Asian and Pacific prehistory, and Sir Sydney Moko Mead, a prominent anthropologist, and Maori elder.

At the close of the 1960s, Mr. Alpert was inspired to explore numerous remote islands in the Malay Indonesian Archipelago. On myriad journeys through the region, he cultivated an intense appreciation for the traditions of the peoples he encountered and for their emblematic artistic canons. These transformative experiences formed the foundation of his expertise as a connoisseur and collector of 'ethnographic' arts.

For decades, Mr. Alpert has participated in stellar museum exhibitions and fruitful collaborations with exceptional area studies specialist scholars. In 1983, The Steven G. Alpert Collection of Indonesian Textiles was inducted into the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA). This acquisition led to a series of shows at the DMA including a major collaborative exhibition entitled "Power and Gold/Woven to Honor," which featured remarkably pristine examples of Island Southeast Asian textiles paired with the groundbreaking Indonesian, Malay, and Filipino gold jewelry collections of Jean-Paul Barbier-Mueller.

In concert with the legendary scholar, Dr. Reimar Schefold, Professor Emeritus of cultural anthropology and sociology at Leiden University, Mr. Alpert edited the book, Eyes of the Ancestors: The Arts of Island Southeast Asia at the Dallas Museum. In 2017, he reunited with Dr. Schefold to assist in the production of an expanded and revised English language rendering of the marvelous work, Toys for the Souls: Life and Art in the Mentawai Islands. Recently, Mr. Alpert has recently completed a chapter for another seminal book, War Art & Ritual: Shields From The Pacific, exploring the lore and art of shields in Borneo. In tandem with notable area specialist, Dr. Antonio Guerreiro, he is working on a significant text focused on the finest antique sculptural arts of Borneo.

Colophon

Authors | © Antonio J. Guerreiro, Steven G. Alpert

Publication | Art of the Ancestors

Date of Publication | January 28th, 2021